Self-Expression

Saturday, April 16, 2016 • 7:30 p.m.

First Free Methodist Church (3200 3rd Ave W)

Orchestra Seattle

Seattle Chamber Singers

Clinton Smith, conductor

Rebecca Nathanson, soprano

Edward Zhang, piano

This concert made possible in part by the Seattle Office of Arts & Culture.

Program

Francis Poulenc (1899–1963)

Gloria, FP 177

Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849)

Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 [first mvmt.]

—intermission—

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

About the Concert

Poulenc’s ability to combine serious ideals with the wit and style of Parisian café society resulted in a unique musical dialect. “I’ve often been reproached about my ‘street music’ side,” he once wrote. “Its genuineness has been suspected, and yet there’s nothing more genuine in me.” Brahms struggled for two decades in the shadow of Beethoven before completing his first symphony at age 43.

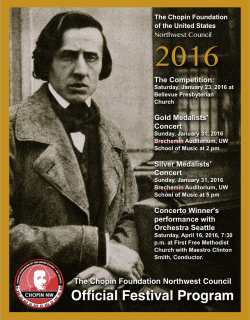

The 2015–2016 season marks our first partnership with the Chopin Foundation of the United States: Edward Zhang, winner of their 2016 Northwest Council competition will perform the first movement of Chopin’s E-minor concerto with Orchestra Seattle.

Behind the Music

Get the inside scoop! Hosted by OSSCS music director Clinton Smith, “Behind the Music” explores who and what inspired composers to create. Enjoy a free, fun and informative half-hour session that includes an overview of the music, historical and cultural context for the works, and highlights to listen for during the performance. Begins at 6:30 p.m. (one hour prior to the performance) at First Free Methodist Church.

About the Soloists

Hailed by Opera News as “particularly vivid” and “nothing short of orgasmic,” soprano Rebecca Nathanson began the 2015–2016 season with an important debut at The Castleton Festival in the title role in Roméo et Juliette. Highlights from last season include her return to LA Opera to cover Violetta in La traviata and Marie Antoinette in the west coast premiere of John Corigliano’s The Ghosts of Versailles, and her debut as Abra in Vivaldi’s Juditha Triumphans at the Palau de les Arts in Valencia, Spain. An alumna of the LA Opera Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist Program, she made her unscheduled mainstage debut as Myrtale in Thaïs with 15 minutes’ notice and covered Renée Fleming as Blanche Dubois in A Streetcar Named Desire. In addition to classical performance, Ms. Nathanson has sung “God Bless America” with Plácido Domingo at Dodger Stadium and was featured with the global phenomenon One Direction in the live broadcast 1D Day. Learn more: rebeccanathansonsoprano.com, @rebeccasongs

Twelve-year-old pianist Edward Zhang began his studies with Ni Liu and Peter Mack, and has been a student of Sasha Starcevich since 2012. He has won several Washington piano competitions and festivals, including first prizes in the 2012–2016 Chopin Festival of the Northwest, the 2011 Seattle International Piano Competition, the 2013 Performing Arts Festival of the Eastside, and the 2012 Russian Music Festival of Seattle, which provided the opportunity to perform in the Nordstrom Recital Hall at Benaroya Hall. Edward was a first-prize winner in the fifth- and sixth-grade solo division of the Eastside Music Teachers Scholarship Competition and was chosen as one of six winners of their Concerto Competition. He placed first in the 2014 Washington State Outstanding Artist Competition, was a concert piano winner in the 2014, 2015 and 2016 Seattle Young Artist Music Festival, and made his debut with Philharmonia Northwest in 2014. He was a winner at the 2015 Russian Music Festival/Competition of Seattle and was chosen to perform in Benaroya Hall and on KING-FM. Edward has been given the opportunity to perform with Orchestra Seattle this evening under the auspices of the 2016 Chopin Foundation of the Northwest, and would like to express his appreciation to the festival for this wonderful milestone in his musical journey. A seventh grader at Evergreen Middle School in Redmond, his hobbies outside of music include reading, swimming and playing chess.

Program Notes

Francis Poulenc

Gloria, FP 177

Poulenc was born in Paris on January 7, 1899, and died there on January 30, 1963. He composed his Gloria between May 1959 and June 1960 on a commission from the Serge Koussevitzky Music Foundation. Charles Munch conducted the premiere in Boston on January 20, 1961, leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Chorus Pro Musica. In addition to solo soprano and SATB chorus, the work requires 3 flutes (two doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, harp and strings.

In a 1950 Paris-Presse article, music critic Claude Rostand described Francis Poulenc—premiere pianist and master of melody—as “monk and rascal” (“le moine et le voyou”). His father, a wealthy pharmaceuticals manufacturer, was a deeply devout Roman Catholic, while his mother’s interests were wide, worldly and artistic, and Poulenc saw in this dichotomy the source of the two apparently contradictory sides of his personal and musical nature. He once described himself as “a melancholic man—who likes to laugh, as do all sad men”; he had long romantic relationships with several male partners during his life, proposed marriage to a childhood friend (she refused his offer) and fathered an unacknowledged daughter with another woman; but following the death of a dear friend and fellow composer in a horrible automobile accident in 1936, his childhood Catholic faith deepened greatly and he composed a number of profound sacred works. His best-known compositions include the ballet Les Biches (The Little Darlings, 1923), a concerto for two pianos and orchestra (1932), the operas Dialogues des Carmélites (1957) and La Voix Humaine (a lyric tragedy for solo soprano and orchestra, 1959), and this Gloria.

His family wanted young Francis to pursue a business career: as a result, he was mostly self-taught as a composer. Through his piano studies with his mentor, Ricardo Viñes, Poulenc came under the influence of eccentric, avant-garde composer Erik Satie and the absurdist author Jean Cocteau, and in 1920 was included in a group of young composers designated “Les Six” after critic Henri Collet published the article “The Five Russians, the Six Frenchmen and Satie.” These musicians were friends and colleagues but not members of a particular “school of composition,” although the music they wrote during the 1920s was, in general, viewed as “neoclassical” (a reaction against the emotional, German romanticism of Wagner on one hand and of French impressionist composers such as Debussy on the other).

As a pianist, Poulenc developed a highly successful performing partnership with baritone Pierre Bernac, and another with soprano Denise Duval. He toured Europe and America with each, and—being among the first composers to appreciate the significance of the gramophone— made many recordings, beginning in 1928. After producing playful, witty, irreverent works for the stage and concert hall, and serious “spiritual” compositions for the church, Poulenc—whose personality and whose music seemed always to blend elements of both the “sacred” and the “profane”— succumbed to a heart attack in 1963. At his funeral in the Church of Saint-Sulpice, organist and composer Marcel Dupré performed on the grand organ, according to Poulenc’s own wishes, the music of Bach, the composer who dedicated his works “to the glory of God alone.”

The Gloria, a rhythmically arresting, contrast-laden and much-celebrated six-movement setting of the text “Gloria in excelsis Deo,” from the Roman Catholic Mass, is perhaps Poulenc’s best-known large-scale composition. The composer’s vivacity and sense of fun, as well as his seriousness and Catholic devotion, are evident throughout this work, which opens with a glittering fanfare featuring pronounced double-dotted rhythms, a foundational figure soon taken up and expanded by the chorus. A frolicsome introduction leads, in the joyous “Laudamus te,” to lighthearted choral cavorting, by voice-pairs of sopranos and tenors playing musical tag with altos and basses, through fluctuating meters and playfully “unnatural”—and thus striking—text accentuations above an “oom-pah” bass. The “Gratias Agimus” text is set for women’s voices and strings with contrasting chromatic seriousness before the chorus’ leaping lines lead to a boisterous conclusion.

To complaints that his Gloria, particularly this second movement, was shockingly irreverent, with its jazzy harmonies, often jagged melodies and general jocularity, Poulenc responded that, while writing it, he had in mind some Gozzoli frescoes showing angels sticking out their tongues, and also some solemn-looking Benedictine monks that he once saw playing soccer; Gozzoli’s angels, however, are actually singing, not making rude faces!

Now the focus shifts from adulatory humans to the Heavenly King. Woodwinds introduce the dramatic “Domine Deus,” in which the luminous soprano soloist is supported chordally by the chorus. The music of the short, sprightly “Domine Fili Unigenite” bursts with sunny energy in a vigorous dance featuring shifting meters and surprising choral accents as God’s earthly children rejoice with the heavenly Son. After a somewhat ominous orchestral introduction, a pensive soprano soloist returns to sing a soaring, somber “Domine Deus, Agnus Dei,” to engage in dialogue with the chorus, and to pray for the mercy of the Lamb of God upon a suffering, sinful world.

The closing “Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris,” which begins with majestic unisons in the voice parts, is punctuated by startling interjections of the first movement’s grand fanfare figure. Throughout the first section, varying voice groupings present the text above the orchestra’s scampering sixteenth notes and a steadily walking bass. The movement’s serene second section begins with the soprano soloist’s firm-but-calm, chantlike “Amen”—Christ the Son is seated at the Father’s right hand—that is loosely imitated by the chorus; it accompanies and responds to her as the text is re-presented, but 10 measures before the end of the work, a triple-forte fanfare and “Amen!” suddenly shatter the ear and the peace. Tranquility is immediately restored, however, and the chorus—and finally the soloist—whisper an affirming “Amen.” In our joys and our sorrows, the Lord indeed has mercy upon us—Gloria!

—Lorelette Knowles

Frédéric Chopin

Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11

Chopin was born March 1, 1810, in Żelazowa (near Warsaw) and died October 17, 1849, in Paris. He began writing this work during March 1830, completing it the following August. Chopin was the soloist at the first public performance on October 11 of that year, in Warsaw.

Although Chopin composed his two piano concertos as vehicles for himself, he played a remarkably small number of public concerts, performing with orchestra for the last time merely five years after premiering these two works. He began composing a concerto in F minor in 1829 and immediately thereafter started work on an E-minor concerto. (Due to their publication in reverse order, the E-minor concerto has become known as Chopin’s Concerto No. 1.)

“I feel like a novice, just as I felt before I knew anything of the keyboard,” the composer wrote while preparing for the premiere of the E-minor concerto. “It is far too original and I shall end by being unable to learn it myself.” Such was not the case. A reviewer who attended a private rehearsal on September 22, 1830, not only praised Chopin’s performance, he described the concerto as “a work of genius,” lauding its “originality and graceful conception” as well as an “abundance of imaginative ideas.”

Johannes Brahms

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

Brahms was born in Hamburg on May 7, 1833, and died in Vienna on April 3, 1897. He began sketching materials for his first symphony as early as 1862, but did not start assembling these ideas in earnest until about 1874. He completed the work during the summer of 1876, while staying at the resort of Sassnitz in the North German Baltic islands; it debuted on November 4, 1876, at Karlsruhe, under the direction of Otto Dessoff. Brahms continued to revise the symphony, particularly the two central movements, over the course of the next year. It calls for pairs of woodwinds plus contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani and strings.

Unlike so many other composers, Brahms took his time creating his first symphony: he was 43 years old at the time of its premiere. Certainly Brahms had the ability to create a successful orchestral work early on, as evidenced by the two delightful serenades that he composed between 1857 and 1859, but these exercises that looked back to Haydn and Mozart were not what Brahms had in mind for a symphony: Beethoven’s shadow hung over his head. Brahms felt compelled to create something that could stand alongside the great masterpieces of his predecessor, and this took time.

At age 21, Brahms heard a performance of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 that spurred him to begin sketching an ambitious symphony in D minor. These attempts proved unsatisfactory and the first two movements eventually became part of Brahms’ first piano concerto, while another found its way into his German Requiem. Beethoven’s Ninth would eventually inform Brahms’ conception of his own first symphony, but so would Beethoven’s Fifth—especially in the choice of key, C minor.

Brahms originally began the opening movement of his symphony at the point where the orchestra now launches into the Allegro tempo—in fact, the composer sent a piano score of the movement to Clara Schumann in this form—but he later added a slow introduction that establishes several of the movement’s important themes; this opening material returns—not quite as slowly—in the first movement’s coda. For the most part, Brahms follows traditional sonata-allegro form, but offers up some surprises as well: ordinarily a C-minor first theme would give way to an E♭-major second theme—it does, but then a violent E♭-minor episode follows, creating a shocking shift of harmonic gears at the repeat of the exposition.

Following a technique he learned from Beethoven, Brahms casts the slow(ish) movement in E major, harmonically far removed from the C minor of the opening movement. These keys, at an interval of a major third, establish a pattern that persists throughout the rest of the work, moving up another major third to A♭ major for the third movement and then to C minor/major for the finale. In his symphonies, Brahms diverged from Beethoven’s model in one important way: in place of a quicksilver scherzo, Brahms opts for a more relaxed third movement, often in 2/4 time (as it is here) instead of the traditional (and much faster) 3/4.

The introduction to the final movement opens slowly and in C minor: following a descending figure from low strings and contrabassoon, the first violins hint at a melody that will soon take on great importance; a pizzicato episode follows and the tempo accelerates, then suddenly relapses as these two ideas are repeated. A syncopated rhythm, swirling from the depths of the orchestra creates great urgency—then the clouds part and a magnificent horn solo signals the arrival of C major. (Brahms had sketched this horn melody on a birthday card to Clara Schumann several years before, attaching the message, “High on the mountain, deep on the valley, I send you many thousands of greetings.”) Next comes a chorale stated by trombones and bassoons, after which the horn call returns, but now developed much more elaborately, subsiding to a simple dominant chord—how will it resolve?

Brahms here introduces his “big tune,” the melody suggested by violins at the opening of the movement, now stated in full. (When someone pointed out to the composer the resemblance of this tune to the “Ode to Joy” melody of Beethoven’s Ninth, the composer is said to have responded, “Any ass can hear that.”) Brahms develops the violin theme, alternating it with other material from the slow introduction, building in fervor. Eventually, the bottom seems to drop out and the tempo slackens for a passionate reprisal of the Alpine horn call. A recapitulation section follows, yet the “big tune” is absent. This leads to a faster coda, which seems intent on driving the movement to its conclusion, but Brahms interrupts with a fortissimo restatement of the trombone chorale from the introduction. A new syncopated triplet rhythm returns the coda to its faster pace and leads to the symphony’s triumphant conclusion.

—Jeff Eldridge