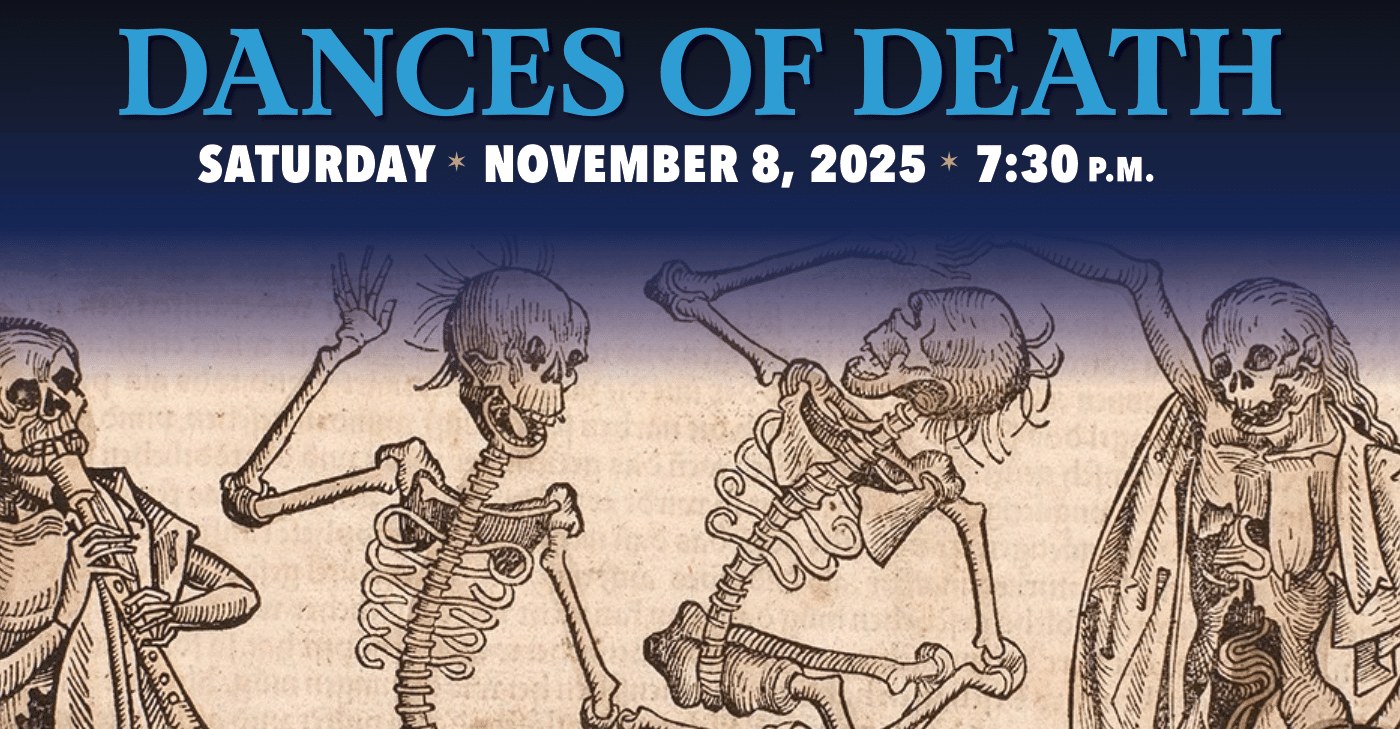

mainstage series

Saturday, November 8, 2025 • 7:30 p.m.

First Free Methodist Church (3200 3rd Ave W, Seattle)

Harmonia Orchestra & Chorus

William White, conductor

Zachary Lenox, baritone

Program

Alfred Schnittke (1934–1998)

“Agitato I” from Story of an Unknown Actor

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873–1943)

“Blessed art Thou, O Lord” from All-Night Vigil

William C. White (*1983)

Dies Irae [world premiere]

— intermission —

Sergei Rachmaninov

Symphonic Dances, Op. 45

- complete concert program (PDF)

About the Concert

With the Symphonic Dances, Sergei Rachmaninov created his final statement, a summary of his life and obsessions, quoting some of the music that meant the most to him: the blazing light of the “Alleluias” from his All-Night Vigil, and the fateful “Dies Irae” melody that had haunted him throughout his career. The “Dies Irae” is also the subject of a major new work for chorus, baritone and orchestra by Harmonia music director William White, receiving its world premiere on this macabre program.

Maestro’s Prelude

Dear Listener,

Hallowe’en comes but once a year. Unfortunately, the date doesn’t line up with our concert schedule, but I see no reason that that should stop me from programming a concert charged with dark energy — and that’s exactly what we have in store tonight.

Let’s start with Rachmaninov, since he’s the major force of gravity on this program. For all that we associate his music with voluptuous, romantic melodies, it’s his sinister, driving textures that have drawn so many of us into his orbit. Rachmaninov was obsessed with death, and we don’t need to know anything about his biography in order to know this fact: he proclaims it loud and clear in his music. For one, he loves a dramatic tam-tam stroke, always a symbol of death in Russian symphonic music. (Join us in February for Tchaikovksy’s Pathétique symphony if you want to hear the locus classicus of this bit of musical symbolism.) But the main giveaway of his morbid mindset is his near-constant allusion to the melody that is most commonly associated with death: the “Dies Irae.”

You’re going to hear the “Dies Irae” tune a lot in tonight’s concert, and that’s by design. This is a program in which the pieces on the first half “add up” to the big work on the second half. The “Dies Irae” is quoted heavily by Rachmaninov in his Symphonic Dances, but that’s not the only tune that he quotes. Rachmaninov was a chronically ill 66-year-old man when he composed the piece, and at least part of him knew that he was writing a testament for posterity. He quotes some of his own earlier works, including a glorious movement from his All-Night Vigil, which you’ll hear tonight in its original choral incarnation.

But what of this “Dies Irae” tune? The song comes from the 13th century and it tells of the end of days. It’s not really about death, per se, but it’s been associated with death for several hundred years because it found its way into the Roman Mass for the Dead (the so-called “Requiem”). To understand more about the connection between the tune and the lyrics of the “Dies Irae,” I bid you read the program notes for my new piece, which will receive its world premiere tonight.

And how does the concert opener by Alfred Schnittke fit into this whole thing? Schnittke is a composer barely known in North America, but he’s a modern legend in Russia, and a well-known quantity in Europe. I happen to be an enormous fan, and I’ve been wanting to bring his music to Harmonia for a while. His dark, zany energy is a big source of inspiration for my own work, and in many ways I think he was the inheritor of the Russian musical tradition of Rachmaninov, Prokofiev and Shostakovich. This little movement sets the stage for a thrill ride of a concert, and I hope you’ll enjoy the experience.

— William White

About the Soloist

Praised for “a broad, resonant baritone that is exquisitely controlled throughout his entire range,”Zachary Lenox has performed across North America, including the roles of Silvio (Pagliacci), Marcello (La Bohème), Marullo (Rigoletto), Count Almaviva (Le nozze di Figaro), Guglielmo and Don Alfonso (Così fan tutte), Papageno (Die Zauberflöte), Father (Hansel and Gretel), Sid (Albert Herring), Gianni Schicchi and Betto (Gianni Schicchi), and Dick Deadeye (H.M.S. Pinafore). He has appeared with Portland Opera Opera Parallèle, Pacific Music Works, Cascadia Chamber Opera, Portland Summerfest, Portland Chamber Orchestra, Portland Concert Opera, Eugene Concert Choir, Bravo Northwest and the Astoria Music Festival. Concert appearances include Handel’s Messiah, Samson and Judas Maccabeus, Haydn’s Lord Nelson Mass, Schubert’s Mass in G, the Verdi and Fauré Requiems, and many works of J.S. Bach, including both the role of Jesus and the baritone arias in the St. Matthew Passion with Harmonia. Engagements during the 2025–2026 season include Orff’s Carmina Burana with both the Vancouver (WA) Symphony and the Willamette Master Chorus, Bach’s BWV 147 with Epiphany Seattle, the role of Mr. Gobineau in Menotti’s The Medium with Ping & Woof Opera, Mozart’s Requiem with the Auburn Symphony, and Handel’s Messiah with Harmonia.

- Learn more: zacharylenox.com

Program Notes

Alfred Schnittke

Story of an Unknown Actor

Schnittke was born in Engels, Russia, on November 24, 1934, and died in Hamburg, Germany, on August 3, 1998. He composed the score for Story of an Unknown Actor in 1976. The 2002 concert version prepared by Frank Strobel includes parts for piano, organ and harpsichord, as well as electric guitar and bass guitar.

The son of a German-Jewish father and a German-speaking mother who hailed from Engels, the capital of the Volga German Republic in the Soviet Union, Alfred Schnittke began studying piano in Vienna when his family briefly moved there in 1946. He subsequently took up musical studies in Moscow, first at the October Music School and later at the Moscow Conservatory, where he remained a student until 1961. He then joined the faculty, working at the institution for another decade. Around that time he also became enamored with serialism, which immediately put him at odds with the Soviet party-line musical establishment. He would eventually embrace a philosophy identified as “polystylism,” in which he juxtaposed musical influences from across the centuries.

With performances of his concert music few and far between, he earned most of his income from cinema, writing 60-plus film scores over three decades. Most of these were Russian movies that gained little exposure in the West — had he been given the opportunity to score films in Europe, he may well have been ranked with such high-profile composers as Ennio Morricone and Michel Legrand.

Story of an Unknown Actor (1976), helmed by prolific Russian director Aleksandr Zarkhi, follows a middle-aged actor in a Siberian theater troupe as he faces the end of his career. Schnittke’s score is largely monothematic, with a single melody heard in a multitude of guises across 12 cues that constitute over a third of the film’s 83-minute running time. “Agitato I” accompanies a montage early in the film, with the melody heard seven times. In each instance, a four-bar introduction precedes the 16-bar theme that consists of four four-bar phrases, all capped by a brief coda.

Sergei Rachmaninov

All-Night Vigil, Op. 37

Rachmaninov was born April 1, 1873, at Semyonovo (near Novgorod), Russia, and died March 28, 1943, in Beverly Hills, California. He composed his All-Night Vigil for unaccompanied chorus in February 1915 for the Moscow Synodal Choir, which gave the premiere on March 15 of that year.

Rachmaninov may have been inspired to create his All-Night Vigil — an hour-long work that he composed over a mere two weeks in early 1915 — by a performance a year earlier of his 1910 Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, which in retrospect he found lacking. He dedicated the Vigil to Stepan Smolensky, former director of the Moscow Synodal School, whose successor Alexander Kastalsy influenced Rachmaninov during the compositional process.

Unlike the Liturgy, which consisted entirely of newly composed Rachmaninov melodies, the Vigil mixes new thematic material with actual plainchants, some of them newer Greek and Kiev chants, but others ancient znameni (from the Russian for “signs”) handed down via oral tradition for centuries and then encoded in special notation, or signs. The 15 movements of the All-Night Vigil consist of six vespers (for an evening prayer service) followed by nine matins (for morning prayer). In the Russian Orthodox Church, these would be sung beginning on the eve of a holy day, from 6:00 p.m. on a Saturday to 9:00 a.m. on Sunday morning.

The ninth movement, “Blessed art Thou, O Lord,” is one of the matins derived from the znameni. Barrie Martyn calls it “one of the most elaborate items in the whole composition and illustrates the way in which Rachmaninov uses countless rhythmic and harmonic variations and choral shadings of a brief chant for a whole narrative. Thus the same flexible formula serves both for the stern opening refrain for tenors and basses … and, contrastingly slower, for the soprano and alto statement of the angel host’s amazement at finding Our Lord alive and for the angel telling the women to look at the tomb.“

Martyn notes that a “particularly delightful feature of this piece is the way in which the different paragraphs are joined by a single held note, usually hummed.”

William C. White

Dies Irae, Op. 68

William Coleman White was born August 16, 1983, in Fairfax, Virginia. He composed this work during the summer of 2025; it receives its first performance this evening. In addition to baritone soloist and chorus, the score calls for one each of piccolo, flute, oboe, English horn, E♭ clarinet, clarinet, bass clarinet, bassoon and contrabassoon, 2 horns, trumpet, bass trombone, tuba, timpani, percussion (flexatone, daluo, suspended cymbal, ratchet, tam-tam, chimes, bass drum, snare drum, finger cymbals and triangle), piano, organ, harpischord and strings, plus two offstage groups (each consisting of a trumpet, horn and trombone) and a processional drum.

William White is of course familiar to Harmonia audiences as the ensemble’s music director. He has provided the follow- ing commentary about his newest composition:

Dies Irae is the third major choral-orchestral work I have composed for Harmonia. The first, The Muses (2022), had as its subject the mystery of artistic inspiration. The second, Cassandra (2024), was about speaking truth to power. The subject of Dies Irae is righteous indignation (and its constant bedfellow, rank hypocrisy).

The Text

The “Dies Irae” is a Latin poem that likely dates from the middle of the 13th century AD. The identity of the poet is lost to the ages, but there is a good chance it was written by Latino Malabranca, a Roman noble and clergyman whose uncle was elevated to the papacy. Malabranca himself attained an exceptionally high rank in the Catholic hierarchy, being named head of the Papal Inquisition in 1278. This was the period during which the Inquisition was at its most zealous, with the church council frequently turning over heretics to local authorities for all manner of medieval punishment. It’s this association that makes me suspect Malabranca as the likeliest of the poem’s authorial candidates, given its themes of revenge and retribution.

In its original form, the poem featured 18 verses of three lines each. At some point in the centuries that followed its initial composition, the final verse was modified, breaking the verse pattern and scansion. What we have now is a poem of 20 verses in which the first 17 flow with a highly regular (and disturbingly sing-song) lilt, and the final three constitute a disjointed appendix.

The poem’s content is, in effect, a gloss on the Book of Revelation: the final, controversial book of the New Testament. The poem distills Revelation’s dark vision of the Day of Judgment, when the Judge of Righteousness (presumably God the Father, but perhaps Jesus) will descend to Earth to separate the wicked from the blessed. In just a few short lines, the poem presents all of the most powerful images associated with this event: the summoning of the dead from their graves, the blast of the trumpet, the heavenly Judge reading his verdicts from “the book in which all is contained,” and the eternal hellfire waiting for those who don’t pass muster.

The Requiem

The next step in this poem’s history is one that I will admit I find altogether perplexing. At some point in the ≈150 years that followed, the poem was subsumed into the Requiem Mass and became a formal part of the Roman Catholic liturgy for the dead. I can only imagine the first time that a (literal) Goth edgelord stood up to read a poem at his dad’s funeral and launched in with, “The day of wrath, that day will dissolve the world in ashes… .” I wish there could have been an Office-style mockumentary to capture the wide-eyed side glances between the other parishioners.

However it happened, the poem became part of the liturgy, and it is in this form that the words have become so well known today. Many great composers have set these words to music as part of their music for the complete Requiem Mass. Mozart’s and Verdi’s settings have even achieved escape velocity and become well known outside the confines of classical music.

The Melody

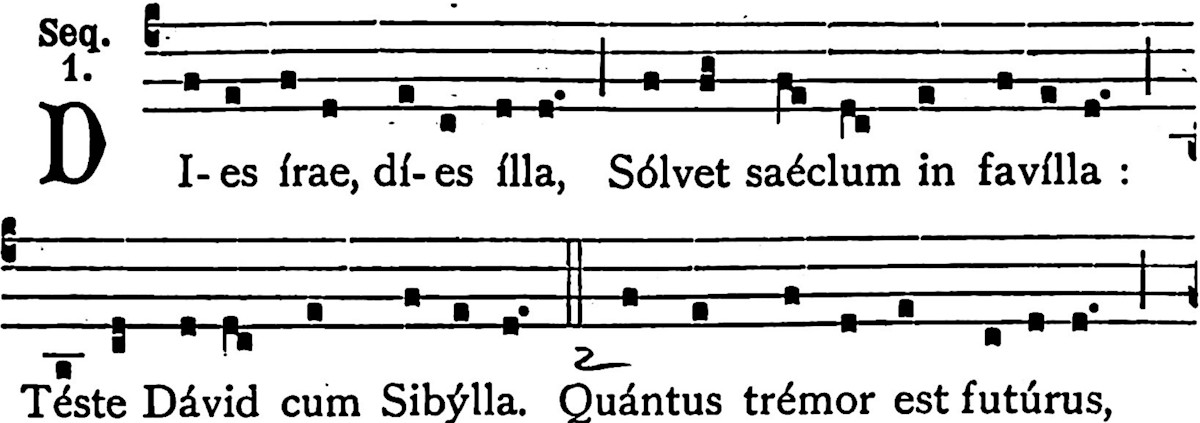

The music of Mozart and Verdi should not, however, be confused with the original musical setting of the words of the “Dies Irae.” The poem was first set to music very early on, probably before the year 1300, as a Gregorian chant:

The tune has gone on to have a life of its own, especially the first eight-note motive, and most especially the first four notes. This little melodic riff has become a musical shorthand for all things related to death and the macabre. It has been quoted — just the notes mind you, not the words — by everyone from Berlioz to Chopin to Brahms to Liszt to Mahler to Shostakovich to Ligeti to Wendy Carlos to Stephen Sondheim. The composer who got the most mileage out of it has got to have been Sergei Rachmaninov, who was obsessed with death and wanted everyone to know it.

The plainchant setting of the “Dies Irae” is, however, not limited to the first eight notes: all 20 lines of the poem are set to music in a rather complicated melodic structure that (bear with me) goes aabbcc aabbcc aabbcdef. The b section (not to mention the c, d, e or f sections) is hardly ever referenced in music by other composers.

Beyond The Requiem

Given the fact that the “Dies Irae” was written as a standalone poem, I find it surprising that it has only rarely been set to music outside the context of the Requiem Mass. In fact, the only instance I know of a composer using the text in this way comes from Jean-Baptiste Lully in 1683.]

I was inspired to set the text while preparing for Harmonia’s performance of the Mozart Requiem in November of 2022. It wasn’t until then that I learned about the history of the “Dies Irae,” and when I found out that it began life as an independent text, it just seemed like the most obvious thing in the world to set it as a standalone composition.

That was all well and good, but then I had a decision to make: whether to set the words to my own original music or to use the pre-existing Gregorian chant melody. And if I did use the chant, would I use the whole thing, or just make occasional allusions to the “head motive” during the piece?

I decided to go for broke. In this piece — with precious few exceptions — the entire chant melody is presented intact, tethered to its original words. As far as I can tell, this hasn’t been attempted since a Requiem setting of Antoine Brumel in 1500, but I can assure you, it has led to exceedingly different results.

The Judge

Not surprisingly for a poem about the day of judgement, the “Dies Irae” makes frequent reference to “Judex,” that is, “The Judge,” but this judge never enters the scene as a “character” per se. That hole at the center of the text makes one wonder, if the judge did show up, what would he say?

This became a pressing issue for me, because early on in my conceptualization of this piece, I decided to include a part for solo baritone, and not just for any solo baritone, but specifically for Zachary Lenox. I had been wanting to write something substantial for Mr. Lenox since he began appearing as a soloist with Harmonia four years ago. I have rarely encountered a bass-baritone (which I’m convinced he really is) who is able to wield such grandeur of sound with such virtuosity of technique.

But I had to decide if the soloist would sing bits of the actual “Dies Irae” text or something else. This resulted in a wild-goose chase, from court verdicts throughout history (including in the Inquisition) to ancient documents concerning justice, and I even considered commissioning a contemporary poet to create something new.

Then on one fateful night, an hours-long session of multi-lingual Googling led me to the perfect text: the anonymous libretto of an obscure Latin cantata by Marc-Antoîne Charpentier titled Extremum Dei Judicium.

Extremum Dei Judicium

Very little information survives about Extremum Dei Judicium (“God’s Last Judgment”). As far as anyone can tell, it was composed in Paris in the 1690s. Charpentier, a middle-Baroque French composer best known for his Messe de minuit (“Midnight Mass for Christmas”) had studied in Rome during the 1660s with Giacomo Carissimi, the Italian composer who basically invented the genre of the Latin oratorio (exemplified by his Jephthe, a favorite of some extremely peculiar people).

Extremum Dei Judicium is exactly what I was after, basically a rendering of the “Dies Irae” into a dramatic scene. (Charpentier referred to his works this genre as “histoires sacrées.”) There are roles for angels, a chorus of the damned, a chorus of the blessed, and — most crucially — God.

It took me ages to track down a source for the actual text of this oratorio, but I was able to find a scan of a handwritten vocal part created for a performance in France in the 1970s. As I started reading the first “Récit de Dieu,” my internal alarm bells began ringing. I typed out the text as quickly as I could so that I could check Google Translate against my barely adequate literacy in Latin.

“Hear, O heavens, what I say, let the Earth hear the words of my mouth. I have looked down from on high upon the children of men to see if there is any that understandeth or seeketh after God: and there is none that doeth good, not one. Wicked and perverse generation, dost thou render this unto thy Lord? Foolish and unwise people, dost thou render this unto thy God?”

Now that’s what I’m talking about!

The Orchestra

I have scored this work for a rather eccentric instrumentarium. First and foremost are three keyboards: piano, organ and harpsichord, a trio highly favored by the Alfred Schnittke, who was, is, and shall remain one of my primary musical inspirations. (I will freely admit that, in many ways, this piece is my version of Schnittke’s Faust Cantata.)

The woodwind section is also unusual, in that there is one of each instrument, but not just one flute, one oboe, etc. I invited all the siblings along, so there’s piccolo, English horn, clarinets in three sizes, and contrabassoon.

The brass section is normal, except that the players are dispersed around the hall in such a way as to make for dramatic effect (which I will not spoil here). The percussion section includes several toys, such as the flexatone, along with certain left-field instruments, such as the daluo (a Chinese ascending-pitch hand gong.)

The Form

The piece is through-composed, but there are definite “movements” within this form: the first six verses of the “Dies Irae” comprise the opening section, followed by an arioso and rage aria for the Judge (in the mode of a manic, bluesy lounge-lizard song).

This is followed by a “slow movement” for the chorus once again, singing the seventh through twelfth verses of the poem. Then we get another arioso for the Judge, followed by a pair of songs for his character in which the chorus also sings. The first of these is the only extended portion of the piece set in the major mode; the second is a “broken mirror” reflection of the first (naturally, in minor), in which I imagined what it would sound like if Elvis were to sing a Verdi aria. In Latin.

The work concludes with a slow-building coda, an unholy benediction, and a final amen.

— William White

Sergei Rachmaninov

Symphonic Dances, Op. 45

Rachmaninov composed this work during July and August of 1940, orchestrating it over the next two months and completing the full score on October 29. Eugene Ormandy conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra in the premiere on January 3, 1941. The score requires triple woodwinds (including piccolo, English horn, bass clarinet and contrabassoon, plus alto saxophone), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, harp, piano, timpani, percussion (triangle, tambourine, bass drum, side drum, tam-tam, cymbals, xylophone, chimes and glockenspiel) and strings.

In addition to four numbered piano concertos and three numbered symphonies (plus a “choral symphony,” The Bells), Sergei Rachmaninov composed a concerto-in-all-but name (the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini of 1934) and one last symphonic foray (the Symphonic Dances of 1940). While these two late-in-life works featured the soaring melodies and lush orchestration for which he was famous, each also exhibited a newfound compactness of form and spikier, more adventurous harmonies. The Symphonic Dances would be Rachmaninov’s final work, the only major piece he composed entirely in the United States.

During the 1930s, Rachmaninov’s career as one of the world’s greatest pianists left less and less time to devote to composition. But he spent the summer of 1940 at a rented estate on Long Island where, writes Michael Steinberg, “there was enough space to allow Rachmaninov a room where he could not be heard composing, that being a condition sine qua non.” He spent the hours between 9:00 a.m. and 11:00 p.m. practicing for his upcoming fall concert tour and writing his first orchestral work since his 1936 third symphony.

After completing a piano score, Rachmaninov wrote an August 21 letter to Philadelphia Orchestra music director Eugene Ormandy announcing “a new symphonic piece, which I naturally want to give first to you and your orchestra,” as a result of the composer’s decades-long association with Ormandy and his Philadelphians. “Unfortunately, my concert tour begins on October 14,” the letter continued. “I have a great deal of practice to do and I don’t know whether I shall be able to finish the orchestration before November.” He was, in fact, able to meet that deadline, completing the full score on October 29, while simultaneously preparing a version for two pianos.

Rachmaninov’s original title for the piece was Fantastic Dances, its three movements called “Midday,” “Twilight” and “Midnight.” He then thought of simply calling it “Dances,” but “was afraid people would think I had written dance music for jazz orchestras.” Ultimately, he dispensed with descriptive movement titles and dubbed the work “Symphonic Dances”: Edvard Grieg, Cyril Scott and Paul Hindemith had all used that term before him, and Leonard Bernstein after, but today “Symphonic Dances” first and foremost brings to mind Rachmaninov.

The concept of a set of orchestral dances may have been inspired by the thought of turning the piece into a ballet. His Paganini Rhapsody had enjoyed much success when choreographed by the Russian-born Michael Fokine (who also happened to be a Long Island resident that summer). Rachmaninov played through the piece for Fokine, who wrote: “Before the hearing I was a little scared of the Russian element that you had mentioned, but yesterday I fell in love with it, and it seemed to me appropriate and beautiful.” A Fokine ballet, however, never came to fruition and the choreographer died two years later.

The opening movement begins quietly, with a simple descending triad that soon explodes into a forceful C-minor statement from the full orchestra, the three descending notes of the triad extending into longer and longer phrases to form a complete melody. The rhythmic opening material eventually subsides, with oboes and clarinets providing simple accompaniment for an expansive E-major melody carried by an alto saxophone. Having never written for the instrument before, the composer consulted famed Broadway orchestrator Robert Russell Bennett. “At that time he played over his score for me on the piano and I was delighted to see his approach … was quite the same as that of all of us when we try to imitate the sound of the orchestra at the keyboard,” Bennett reported. “He sang, whistled, stamped, rolled his chords, and otherwise conducted himself not as one would expect of so great and impeccable piano virtuoso.” (For the bowings in the score, Rachmaninov consulted none other than the violin virtuoso Fritz Kreisler.)

Strings take up the soaring saxophone melody, leading to a recapitulation of the opening material. In a brief but remarkable coda, Rachmaninov quotes a theme from his disastrously received Symphony No. 1 of 1897, recasting a minor-mode march motive into a luscious C-major melody. The movement ends much as it began: quietly, and dominated by the descending triad from the opening bars (albeit now in C major).

Muted brass instruments introduce the central movement, which soon establishes itself as a valse fantastique, but in 6/8 and 9/8 meter rather than the traditional 3/4, allowing for an ebb-and-flow pulse compared to the more regular beat of waltz time. Here Rachmaninov mixes sugary-sweet Romanticism with melancholy chromaticism. “These waltzes are not festive, but resigned and anxious by turn,” writes Steven Ledbetter, who compares this movement to Ravel’s La Valse and Sondheim’s A Little Night Music, “the harmonic turns of which recall Rachmaninov’s waltz etched in acid.”

After a brief, slow introduction, the finale (also predominantly in 9/8 and 6/8) is dominated by syncopated rhythms with displaced accents that suggest Stravinskian mixed meters, followed by a more malleable central episode. Rachmaninov eventually introduces two melodies that battle against each other: the first is from “Blessed art Thou, O Lord” in his 1915 All-Night Vigil, and the other is the “Dies Irae,” which had featured in a number of his major works over the previous decades. Near the end, the composer writes “Alliluya” in the score at the point where he quotes the “Alleluia” passage from “Blessed art Thou, O Lord.”

Although Rachmaninov was already suffering from health issues that would lead him to move to Beverly Hills for its warm climate and proximity to musical friends and colleagues, it is difficult to state with certainty that the Symphonic Dances constituted a conscious final statement, but it functions as a magnificent one, nevertheless.

— Jeff Eldridge