From Russia With Love

Saturday, October 8, 2016 • 7:30 p.m.

First Free Methodist Church (3200 3rd Ave W)

Orchestra Seattle

Seattle Chamber Singers

Clinton Smith, conductor

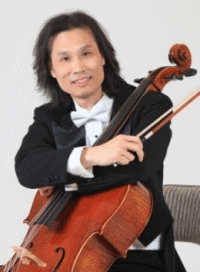

Kai Chen, cello

Julia Benzinger, mezzo-soprano

Program

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844 –1908)

Russian Easter Overture, Op. 36

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 –1893)

Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op. 33

— intermission —

Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953)

Alexander Nevsky, Op. 78

About the Concert

Prokofiev’s powerful Alexander Nevsky cantata, drawn from his score for Sergei Eisenstein’s cinematic masterpiece, recounts a 13th-century battle between Russian forces and Teutonic invaders — from the thrilling “Battle on the Ice” to the haunting “Field of the Dead.” Equally picturesque, Rimsky-Korsakov’s festive Russian Easter Overture evokes the sounds of Russian Orthodox chants and celebratory church bells. Cellist Kai Chen joins Orchestra Seattle for Tchaikovsky’s charming Rococo Variations, a musical tip of the hat to his idol Mozart.

Please join us prior to the concert at 6:30 p.m. for a free “Behind the Music” discussion!

About the Soloists

Internationally renowned cellist Kai Chen was recognized as one of most distinguished cello solo artists in China prior to his immigration to the United States in 2001. He frequently appeared as a featured soloist with the China National Opera Theater Orchestra (CNOTO), the Shanghai Symphony and the Beijing Symphony. He has performed throughout Asia and Europe and released several highly acclaimed recordings featuring chamber music of Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Mozart. Mr. Chen performed as principal cellist with CNOTO, the Beijing New Millennium Chamber Ensemble, the Beijing Principals Orchestra and numerous chamber music ensembles. In his final two years with CNOTO, he functioned as the associate artistic director, overseeing the entire June 2001 production of The Three Tenors in the Forbidden City. Over the past 15 years, Mr. Chen has become extensively involved as a freelance musician, recitalist and master cello instructor in the greater Seattle area. He has performed in the Federal Way Symphony, the Northwest Mahler Festival, Bellevue Philharmonic and various chamber ensembles, and was featured as soloist with the Puget Sound Symphony. He currently performs in the Tacoma Symphony. Mr. Chen graduated with honors from the Central Conservatory of China in 1987.

Mezzo-soprano Julia Benzinger, hailed by the International Herald Tribune for her “luscious mezzo” and Der Tagesspiegel for “her impressive, metallic dramatic soprano,” enjoys a career in both opera and concert throughout Europe and the United States. During the 2016 –2017 season, she sings Mére Marie in Dialogues des carmélites with Vashon Opera, performs John Cage’s radical compositions Aria, 5 Songs for Contralto and Sonnekus at Town Hall, and appears as the Sorceress in Dido and Aeneas with Pacific MusicWorks. From 2007 through 2012, Ms. Benzinger was a member of the ensemble of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, where her roles included Der Komponist (Ariadne auf Naxos), Flosshilde (Das Rheingold) and the title role in Gnecchi’s Cassandra, all under the baton of Donald Runnicles. Her performance of the title role in Carmen for the Oldenburg Promenade prompted the Märkische Oderzeitung to write: “Julia Benzinger was charged with bringing the incredible fire and passion of the Gypsy Carmen to life. And that’s just what she did.” Her concert repertoire includes works of Bach (Magnificat, St. Matthew Passion, Christmas Oratorio), Beethoven (Ninth Symphony), Brahms (Alto Rhapsody), Elgar (Sea Pictures), Handel (Messiah), Mendelssohn (Elijah) and Rossini (Stabat Matter).

Program Notes

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Russian Easter Overture, Op. 36

Rimsky-Kosakov was born March 18, 1844, in Tikhvin, Russia, and died near St. Petersburg on June 21, 1908. He began composing this overture on August 6, 1887, finishing it on April 1 the following year and conducting the premiere in St. Petersburg on December 15, 1888. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds (plus a third flute doubling piccolo), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, tam-tam, triangle), harp and strings.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov trained for a naval career, but after a 30-month voyage with ports of call in America (during the Civil War), Brazil and Europe, he gravitated toward music. Eventually acknowledged as an unrivaled master of orchestration, he influenced two generations of Russian composers (including Stravinsky) as well as Ravel, Debussy and Respighi. Along with a penchant for “cleaning up” the rough edges in music of Borodin and Mussorgsky after their deaths, he composed 15 operas, three symphonies, choral works, chamber music and art songs. Today he is most often represented on the concert stage by a trio of orchestral works that he unveiled within the span of a year: Capriccio Espagnol, Scheherazade and the Russian Easter Overture.

In his 1909 autobiography, My Musical Life, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote about composing “an Easter overture on themes from the Obikhod,” a collection of Russian Orthodox liturgical chants first printed in 1772. “The rather lengthy slow introduction of the Easter Sunday overture, on the theme ‘Let God Arise!,’ alternating with the ecclesiastical theme ‘An Angel Cried,’ appeared to me, in the beginning, as Isaiah’s prophecy of the resurrection of Christ. The gloomy colors of the Andante lugubre seemed to depict the holy sepulchre that had shone with ineffable light at the moment of the resurrection — in the transition to the Allegro of the overture.

“The beginning of the Allegro, ‘Let them also that hate Him flee before Him,’ leads to the holiday mood of the Orthodox church service on Christ’s matins. The solemn trumpet voice of the Archangel is then displaced by a tonal reproduction of the joyous, dance-like tolling of the bells, alternating with an evocation of the sexton’s rapid reading and the chant of the priest’s reading the glad tidings of the Evangel. The Obikhod theme, ‘Christ is risen,’ which is the subsidiary part of the overture, appears amid the trumpet-blasts and bell-tolling, constituting a triumphant coda.

“In this overture were thus combined reminiscences of the ancient prophecy, of the gospel narrative, and also a general picture of the Easter service with its ‘pagan merry-making.’ The capering and leaping of King David before the Ark, do they not give expression to the same mood as the idol-worshippers’ dance? Surely, the Russian Orthodox Obikhod is dance music of the church. And do not the waving beards of the priests and sextons clad in white vestments and surplices, intoning ‘Beautiful Easter,’ transport the imagination to pagan times? And all those Easter loaves and the glowing tapers! How far a cry from the philosophic teachings of Christ! The legendary and heathen side of the holiday, the transition from the gloomy and mysterious evening of Passion Saturday to the unbridled pagan-religious merrymaking on Easter Sunday morning is what I was eager to reproduce in my overture.”

To preface his overture, Rimsky-Korsakov commissioned a poet, Count Golenishchev-Kutuzov, “to write a program in verse — which he did for me. But I was not satisfied with his poem, and wrote in prose my own program, which same is appended to the published score. Of course, in that program I did not explain my views and my conception of the ‘Bright holiday,’ leaving it to tones to speak for me. Evidently these tones do, within certain limits, speak of my feelings, and thoughts, for my overture raises doubts in the minds of some hearers, despite the considerable clarity of the music. In any event, in order to appreciate my overture, even ever so slightly, it is necessary that the hearer should have attended Easter morning service at least once, and, at that, not in a domestic chapel, but in a cathedral thronged with people from every walk of life, with several priests conducting the cathedral service — something that many intellectual Russian hearers, let alone hearers of other confessions, quite lack nowadays. As for myself, I have gained my impressions in my childhood passed near the Tikhvin Monastery itself.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op. 33

Tchaikovsky was born in Votkinsk, Russia on May 7, 1840, and died in St. Petersburg on November 6, 1893. He composed this theme and variations in December 1876. Nikolai Rubinstein conducted the premiere in Moscow on November 30, 1877, with Wilhelm Fitzenhagen as soloist. Fitzenhagen subsequently revised the work, which (in addition to solo cello) requires pairs of woodwinds and horns, plus strings.

Just how Tchaikovsky decided to compose a work for cello and orchestra remains unclear, but he wrote it quickly in December 1876, shortly after the “brilliant failure” of his opera Vakula the Smith in St. Petersburg — on top of news from Paris and Vienna about poorly received performances of his tone poem Romeo and Juliet. An ardent admirer of Mozart (“It is thanks to Mozart that I have devoted my life to music”), Tchaikovsky would later adapt Mozart melodies into an 1887 orchestral suite, but for his set of variations for cello and orchestra the Russian composer crafted an original theme, in the form of a gavotte inspired by the style of Mozart’s late-18th-century Rococo period.

In January 1877 Tchaikovsky showed the piano score of his variations to the young German cellist Wilhelm Fitzenhagen, a colleague at the Moscow Conservatory, who participated in the premieres of all three of the composer’s string quartets. Fitzenhagen penciled many alterations into the cello part and Tchaikovsky subsequently orchestrated the work with these changes intact. It was Fitzenhagen who premiered the Rococo Variations at the end of November, eliciting a positive response from audience and critics.

Tchaikovsky himself did not hear the first performance (he was abroad at the time), after which Fitzenhagen took it upon himself to perform some major surgery on the structure of the piece. Apparently seeking to exploit the popularity of Tchaikovsky’s third variation, a D-minor Andante, the cellist moved it near the end of the work, placing it as the penultimate variation. He also swapped the order of two others and omitted the original eighth variation entirely. “Loathsome Fitzenhagen! He is most insistent on making changes to your cello piece,” wrote Tchaikovsky’s publisher in February 1878 while preparing the piano reduction for publication, “and he says that you have given him full authority to do so. Heavens!” Perhaps due to the fallout of his ill-fated marriage, Tchaikovksy failed to object at the time.

A decade later, prior to the 1889 publication of the orchestral score for the Rococo Variations, he told a cellist friend, “Look what that idiot Fitzenhagen did to my piece, he altered everything!” Nevertheless, he declared: “The devil take it! Let it stand as it is!” Thus Fitzenhagen’s version of Tchaikovsky’s miniature masterpiece has graced concert halls around the world ever since, standing with the concertos of Schumann, Dvořak and Elgar as the most commonly performed — and best-loved — works for cello and orchestra in the repertoire. (In 1941 Soviet musicologists published a reconstruction of Tchaikovsky’s original, which in recent years has received a handful of recordings.)

Following a brief orchestral introduction, the soloist states Tchaikovsky’s graceful theme, supported by strings, leading to a short codetta for woodwinds that will recur as a bridge passage throughout the work. The first two variations retain the meter (2/4) and key (A major) of the theme, while the third variation — in C major and a slower triple meter — allows for a beautifully expressive solo line. The next two variations return to the opening key and meter, with a cadenza leading to the D-minor Andante, followed by a virtuoso final variation and brilliant coda.

Sergei Prokofiev

Alexander Nevsky, Op. 78

Prokofiev was Born in Sontsovka (Ukraine), of Russian parents, on April 23, 1891, and died in Moscow on March 5, 1953. He composed music for the film Alexander Nevsky in 1938, preparing this cantata the following year and conducting the premiere in Moscow on March 7, 1939. In addition to mezzo-soprano soloist and chorus, the cantata calls for: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, tenor saxophone, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp and strings.

During February and early March of 1938, Sergei Prokofiev traveled across the United States on a concert tour. After his last engagement, as piano soloist with the Denver Symphony, he responded to an invitation to make an unscheduled trip to Hollywood, his second to the nation’s movie capital. During his stay he visited several studios, taking a keen interest in their recording techniques.

Prokofiev had previously expressed his admiration for the 1937 release Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, so he jumped at the chance to meet with Walt Disney. Looking for additional musical material for the forthcoming Fantasia, “le papa de Mickey Mouse” (as Prokofiev referred to him) inquired about acquiring film rights to the composer’s 1936 composition Peter and the Wolf (which would eventually find its way into the 1946 Disney release Make Mine Music).

At Paramount Pictures — where he observed composer Dimitiri Tiomkin recording source music for Henry Hathaway’s Spawn of the North — Prokofiev received an offer for 10 weeks of employment in exchange for “a nice big sum.” The composer’s schedule did not allow him to accept, but he promised to return the following year. Sadly, due to the onset of World War II and Prokofiev’s failing health, he would never again set foot outside the Soviet Union.

The following month, back in the USSR, Russian director Sergei Eisenstein asked Prokofiev to score his newest film project: Alexander Nevsky, the story of a 13th-century prince who successfully leads an army of Russian peasants, defending against a German invasion. The choice of this historic battle as a cinematic subject was not a mere whim: Stalin intended the film to be used as anti-German propaganda. “The late 1930s and 1940s were the golden era for the Stalinist biopic,” notes Kevin Bartig in Composing for the Red Screen: Prokofiev and Soviet Film, “a genre that cast members of the Russian historical pantheon in roles that sculpted contemporary Soviet identity.” Both Eisenstein and Prokofiev had suffered recent failures (at least in the eyes of Soviet artistic bureaucrats) and needed to redeem themselves with authorities, so they agreed to participate despite the openly propagandist nature of the project.

In the United States, composers ordinarily did not score a picture until quite late in the filmmaking process (aside from the animated features Prokofiev admired), but Eisenstein had established a much different approach on his previous movies. For Alexander Nevsky, Prokofiev visited the sets and viewed daily rushes, in some cases composing cues before the film was edited, allowing the director to match his images to the music — and in at least one instance writing music for a scene before it had been shot.

Alexander Nevsky premiered on December 1, 1938, receiving acclaim from audiences as its release spread throughout the USSR. By mid-April 1939, a government official claimed over 23,000,000 people had seen the film. On August 23, Stalin signed a non-aggression pact with Hitler, rendering all anti-German propaganda unwelcome, so the film was shelved until 1941 — at which time it helped fan the flames of anti-German sentiment, while coming to be regarded as one of the most important films of its era.

Nevsky’s famous 30-minute battle sequence has influenced everything from Laurence Olivier’s Henry V (1944) to the original Star Wars films. (In particular, the white-caped, metal-helmeted Teutonic knights prefigure George Lucas’ stormtroopers, while a particularly evil-looking monk is a dead ringer for the Emperor in Return of the Jedi.) Likewise, Prokofiev’s music inspired generations of film composers (perhaps most strikingly James Horner’s “Battle in the Mutara Nebula” cue from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan).

Not long after Alexander Nevsky’s premiere, Prokofiev reworked much of his score into a cantata, combining various cues to form longer movements but maintaining the chronology of the film. It has become one of the hallmark choral-orchestral works of the 20th century and one of Prokofiev’s most popular compositions.

“Russia Beneath the Yoke of the Mongols” serves as an instrumental overture, musically depicting a desolate landscape strewn with remnants from past battles. Mongol warriors have attempted to menace Alexander and his compatriots, but the Russian prince fends them off, warning of more dangerous aggressors from the west: the Germans. Russian peasants sing a “Song about Alexander Nevsky,” praising his slaughter of an invading Swedish army two years prior.

“The Crusaders in Pskov” opens with that city falling to attacking German forces, who attempt to forcibly convert Russian peasants to the Roman form of Christianity, singing a Gregorian chant of Prokofiev’s own invention. (The chant’s text is grammatically inept: either Prokofiev was not well versed in Latin or, as Morag Kerr has theorized, Prokofiev strung together words arbitrarily chosen from Igor Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms — a dig at his older colleague.) German soldiers burn alive town officials and small children alike.

The townspeople of Novgorod sing “Arise, People of Russia” as Alexander prepares his army for battle.

“The Battle on the Ice,” the film’s monumental set piece, forms the cantata’s longest and most dramatic movement. Prokofiev combined several separate cues with newly composed material to depict the great confrontation. The movement opens quietly, the composer evoking the bitter cold on the frozen Lake Chudskoye. The German soldiers’ battle chant emerges, as if from a distance. The Teutonic forces approach on horseback and engage the Russians. Slashing gestures underscore hand-to-hand swordplay. Eventually, Alexander faces the German commander in a one-on-one confrontation. When the ice begins to crack under the weight of the heavily armed forces, most of the German army slides into the freezing lake. Russian peasants stare in astonishment at the aftermath of the battle.

In “The Field of the Dead,” soldiers lie expired and dying on the battlefield. Earlier in the film, a young woman had promised two warriors she would marry the one who proved himself bravest in combat. As she wanders about searching for her suitors, a mezzo-soprano sings her heartbreaking lament. The woman eventually finds the pair alive but wounded, one gravely so; she helps them stagger away. Back in Pskov, citizens kneel before a funeral procession.

Clanging bells and a joyous song greet “Alexander’s Entry into Pskov.” Townspeople dance to playful music and sing in celebration of the great victory.

—Jeff Eldridge